Language for School

As a Speech Pathologist, one of the most common concerns that I see at the Cooee clinic is language concerns in the school age population.

But just what skills do students need to be able to independently and functionally participate in academic and social activities at school?

This is a large area encompassing many skills. When we hear the word ‘language’, quite often we just think about making sentences and following directions; but it is so much more than that.

This blog is going to discuss a few key elements relating to language skills needed for school aged students.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary enables us to interpret and to express. If you have a limited vocabulary, you will also have a limited vision and a limited future.

~ Jim Rohn.

Vocabulary plays a very important role for all levels of reading. Continuing to build your child’s vocabulary throughout their reading journey will provide them with the skills to learn new information!

Vocabulary at the start of the journey – Beginner readers:

Need a wide variety of words in their speaking vocabulary to support their ability to recognise the words they decode/sound out from written text. When little ones are learning to read and are sounding out the letters of a new word, they will be able to recognise the sounds as matching familiar words they already know – words that are in their vocabulary. As children continue reading and recognising these words in their vocabulary, this enhances their recall and therefore also reading fluency – creating an efficient reader.

Without a well-established verbal vocabulary, children may struggle to make meaning of the word/s they are reading. This may impact recognition of these same words as they continue reading.

Continuing the journey -In the mid-primary school years and beyond:

Classroom teaching evolves to rely on reading in order for children to fully access their school curriculum. Therefore, it is expected that children are efficient readers and are able to accurately and fluently read through passages of text. For our advanced readers in later primary and high school years, understanding a variety of tier 2 & 3 vocabulary is essential to reading comprehension. Having a vast vocabulary of words will enhance the child’s ability to absorb the content they are reading.

Furthermore, in possessing a vast vocabulary of words, children will be able to use the meaning they are able to interpret from their reading to learn new vocabulary that is often not used in verbal communication (otherwise known as tier 2 words).

Consider the following passage, adapted from “The Colors of Animals” by Sir John Lubbock in A Book of Natural History (1902, ed. David Starr Jordan):

“The color of animals is by no means a matter of chance; it depends on many considerations, but in the majority of cases tends to protect the animal from danger by rendering it less conspicuous. Perhaps it may be said that if coloring is mainly protective, there ought to be but few brightly colored animals. There are, however, not a few cases in which vivid colors are themselves protective. The kingfisher itself, though so brightly colored, is by no means easy to see. The blue harmonizes with the water, and the bird as it darts along the stream looks almost like a flash of sunlight.”

This passage contains a variety of tier two words, which are important for efficient reading comprehension. With parent-/teacher-support, a child will be able to use their knowledge of the common tier one words (such as colour, animal, blue, easy) and the context of the information to build a definition of new complex tier two words (such as considerations, rendering, vivid, harmonizes, conspicuous). Tier 3 words are domain specific vocabulary. Think scientific, medical and mathematical language that will only be encountered during learning about those topics. Explicitly highlighting and discussing this new vocabulary with your child will continue to build their repertoire of words and enhance their access to and production of written language.

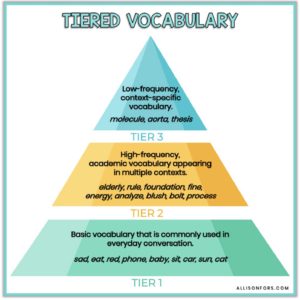

Tiers? Of vocabulary? What are these?

The tiers of vocabulary help us know what words are important and may need to be explicitly taught to students.

As mentioned above, there are 3 tiers.

Image accessed from Alison Fors Speech Therapy tools, https://allisonfors.com/tiered-vocabulary/, on 9 September, 2024. (The three-tier framework was developed by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown and Linda Kucan, 2013)

Tier 1: Common words

Tier 1 words include the everyday, familiar words that are easily understood and can be learned through exposure in conversation and everyday experiences. These are words that are part of most children’s vocabulary. Examples include: house, cat, big, small, table, fun, party.

Words students already know.

Tier 2: High-frequency academic words

Tier 2 words are frequently occurring words, which occur in academic texts across many different subject areas. These play an important role in understanding the information; not knowing what these words mean can impact comprehension and performance. Examples include justify, explain, expand, predict, summarise, maintain, compare, contrast, synthesise, combine.

Words students should and need to know.

Tier 3: Low frequency, domain specific words

Tier 3 words are words we don’t come across everyday. They are specialised, not seen regularly and are only required in their specific fields. These words are taught as needed for understanding in specific content areas. Examples include algorithm, binary, geometric, hyperbole, photosynthesis.

Words students could know.

Impacts for vocabulary instruction

When selecting words for specific vocabulary instruction, using the tiers can help. A great starting point for selecting words to talk about is tier 2 words. Tier 2 words are words in the sentence that if you don’t know what it means or what it means in that context, it can change the way that sentence is understood.

So, how do we teach new words?

A powerful tool for teaching new words to children and students is The Four-Square or Quadrant approach to teaching vocabulary. This is based upon Frayer’s graphic organiser model (Frayer et al, 1969), which divides the paper into 4 boxes.

The basic premise is that the word is taught through 4 elements. These elements are changeable, depending on the context, the age of the child and what approach you look at.

To teach vocabulary:

- Talk about the sound elements in the word – the number of syllables, the first sound, the last sound, if there are any consonant blends, if there are any prefixes and suffixes etc.

- Make sure the child writes/says a definition in their own words. Look up a dictionary definition and have them write it in their own words – if they don’t understand the words in the definition – they won’t understand the definition!

- Talk about related words – words that are similar to the target word

- Talk about opposite words – words that mean the opposite to the target word.

This Four – Square/Quadrant approach can be used to teach both tier 2 and 3 words.

Instruction should begin with unknown tier 2 words in books, textbooks and schoolwork.

TIP: A great way to know which words you need to help your child/student understand is when working together; write down any unknown words onto pieces of paper and pop it in a word jar. Once schoolwork is complete, choose a word from the jar and apply The Four-Square Strategy to help them to understand the word.

Another key element for language at school is discourse level language. This also encompasses sentence complexity.

Discourse level language

Discourse is the way that language is used to construct connected and meaningful texts, either spoken or written. It is a view of language, therefore, that extends ‘beyond the sentence’. Discourse applies to written, spoken and conversational language.

This is the stage of language that people use to deliver a whole range of ideas in an organised manner, whether the choice is writing or speaking. This includes the ability to use higher level language skills, particularly inference and summarisation. There is also an element of lexical cohesion or the way words have been chosen to link information, that is required to utilise and understand discourse or connected language.

As students progress through the schooling years, they are exposed to and are expected to use the four main discourse types:

- Description: This type of discourse relies on descriptions to build imagery to help the reader or listener visualise something – a scene, an item, etc. Might include description of sounds and feelings to help ‘set the scene’.

- Narration: Storytelling. Stories can be fiction or nonfiction. This discourse is particularly important for social interactions. Personal stories form the basis of all interactions.

- Expository: Informative, fact-based piece. The goal is simply to educate, not to persuade or influence the reader/listener.

- Argumentative: Persuasive writing, negotiation. The goal is to influence the reader/listener to agree with your position. It uses logic to demonstrate the author’s point of view and persuade the reader/listener to agree. It guides the reader/listener to form their own opinion.

(https://www.grammarly.com/blog/discourse/)

Conversation tends to flow between the above discourses; with the addition of pragmatic (social) skills and knowledge.

Why is discourse level language important? – because this is how students show what they have learned, through writing or speaking.

The ability to understand/comprehend connected (discourse level) language is influenced by many speech and language based factors, including:

-

- Sounds – consonants, vowels, phonemes etc.

- Pitch, loudness, length of the sounds

- Appropriate sentence structure

- Adequate complexity of sentences

- Semantic or vocabulary variation and relevancy

- Pragmatic (social communication) aspects in conversation (https://www.rit.edu/ntid/slpros/assessment/intel/discourse)

Sentence complexity

Sentence complexity is how complex in terms of structure a sentence is. A complex sentence is defined as a sentence with one independent clause and at least one dependent clause (Grammarly, 2024). Complex sentence types include coordinating conjunctions (ie. for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) and subordinating conjunctions (ie. because, while, since, when, before, after, as, although, if, until etc.).

Sentences with a coordinating conjunction are known as compound sentences and those with a subordinating conjunction are known as complex sentences. An easy way to tell the difference is in a compound sentence, each part of the sentence can stand alone, whereas in a complex sentence, the dependent clause cannot.

Example compound sentence: I went for a run but it was raining.

Here, both “I went for a run”, and “It was raining” make sense on their own.

Example complex sentence: Although she was late, she stopped for coffee.

Here, the dependent clause (although she was late) doesn’t make sense and isn’t complete on its own.

Complex sentences are especially important for discourse level language, as they express the interaction and relationship between ideas and thoughts and allow these to be described (Steel, Rose and Eadie, 2013). Narratives/stories especially, with limited complex sentences are therefore less complex in nature and overall structure, as students are unable to express the links between ideas cohesively or in a manner that makes sense to the reader/listener.

Vocabulary, discourse level language, sentence complexity – you may be thinking “But how do we know when students are meant to develop these skills? – How will my child develop literate language?”

Westby (1985) proposed the development of discourse level language happens along an “Oral to Literate Continuum”. Simply put, they start with spoken connected language discourse and increase in complexity to written language contexts. Language moves from conversational and informal to academic and formal. The continuum includes conversation, narration, exposition; from the “here and now” to the “there and then” (Paul, R. & Norbury, C., 2012).

(Image accessed from https://mindwingconcepts.com/pages/research)

The below pair of sentences demonstrates the difference between the oral/conversation level and literate/written level.

Oral:

We had lunch, then we went to see a movie.

Literate:

After the meal was eaten, all of the participants viewed a film.

The oral-literate language continuum demonstrates the importance of each type of discourse in order to develop a student’s language skills, from informal, verbal conversation to formal, academic written language.

If your child is struggling with any element of language, please get in touch with our client care team today and book in a Client Journey Planning session with our Speech Pathologists to determine what may be needed to support your child on their journey to literate language.

Emma Lefever

Speech Pathologist & Clinical Lead